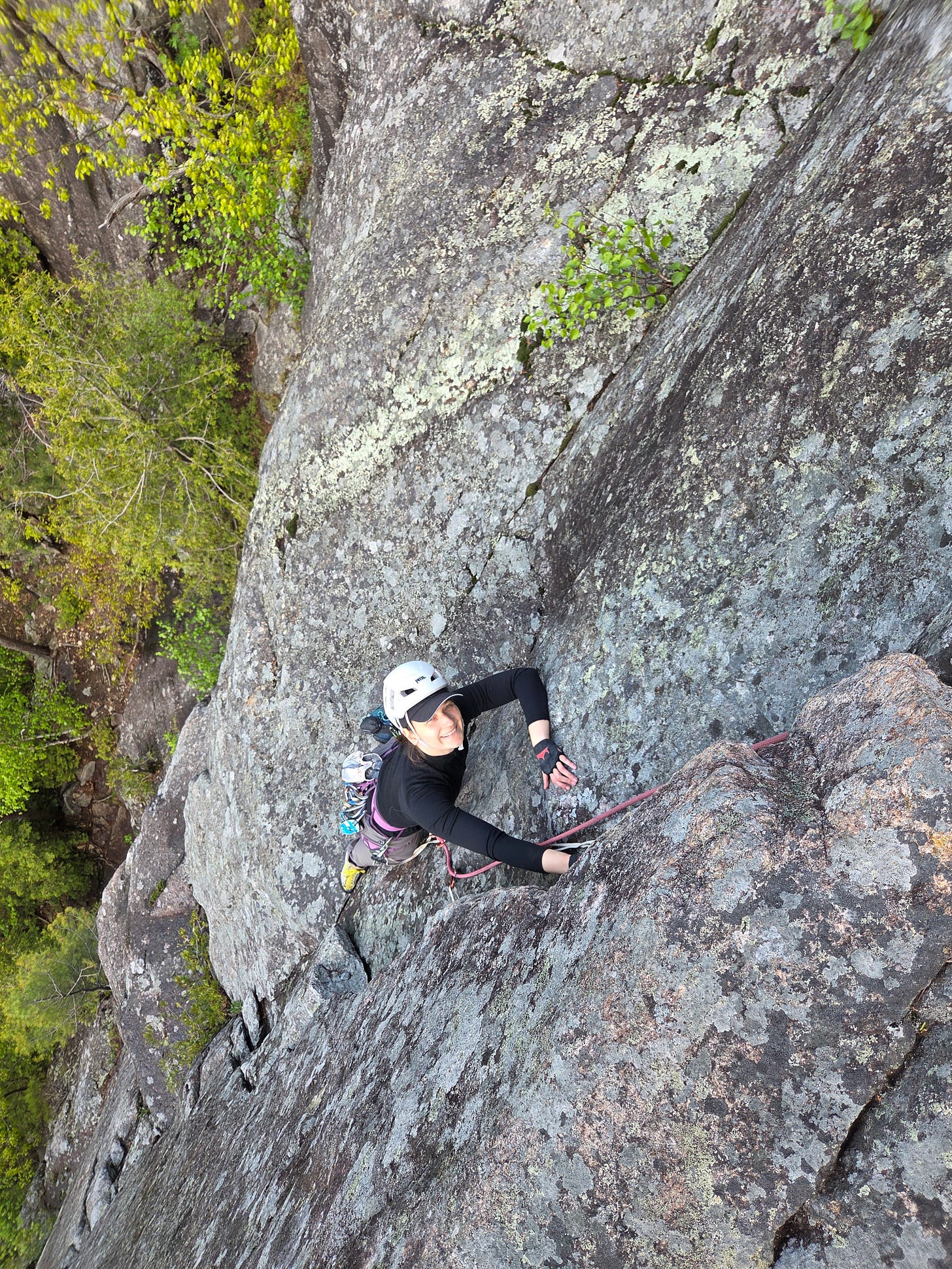

Climbing an Adirondack Classic Multi Pitch: "Quadrophenia" (5.7+)

How navigating subpar conditions can offer a fuller value outing

There’s a popular saying, “Any day of skiing is better than no day of skiing.” Or something like that. The phrase is meant to highlight the silver lining that can emerge during a ski day with poor conditions.

Despite the cold. Despite the crappy snow, and lack of sun, or whatever, you’re still out enjoying skiing, and that’s always better than not skiing at all.

I am inclined to agree with the phrase. I’ve said it myself many times. I am also inclined to agree that the phrase works for rock climbing.

Any day of climbing is better than no day of climbing.

On Memorial Day, the holy trifecta of (1) good weather, (2) Whitney’s free time, and (3) my free time aligned. So we took advantage. We blasted north to the Adirondacks to try a classic multi-pitch route called Quadrophenia (5.7+).

The forecast for the day looked ideal, so we weren’t worried about that. But there had been some rain in the previous days and even the night before. Plus, Spring in the Dacks is notoriously wet (and muddy). Therefore, we were unsure whether we’d find dry rock when we arrived at the route. And we were frightened by the prospect of trudging through sludge just to get there in the first place.

On the way up the short, steep approach from Highway 9N, we found a lot of water. The trail was running with water in certain sections, and lower cliff bands were seeping and dripping with fresh spring runoff and rainwater. Nonetheless, we kept hiking.

What we found at the base was disheartening. The first pitch was wet. Like really wet. I couldn’t see any running water, but the whole thing was opaque black, soaked, and stained. The problem was that while most of the upper cliff faces southeast and gets a lot of sun for drying, the first pitch was tucked down in a corner and facing west.

The other problem was that the entire route followed an impressive crack system leading from the ground to the summit. Cracks, or weaknesses in the rock, come from erosion. In the case of Quadrophenia, the crack likely formed due to water erosion and freeze-thaw cycles. Once formed, crack systems function as ideal pathways for water drainage as water is pushed off the top of the mountain by gravity and back down toward the ground.

After some dillydallying, we decided to climb the route anyway. But we didn’t just go whole hog and blast off into the wet rocky abyss. We put together a plan.

The Plan

The plan was to climb the first pitch and then reassess. We felt okay about this because, based on the terrain in front of us and what we read in the guidebook, we knew we could get down after the first pitch without committing to the rest of the route if it turned out to be too heinous.

The plan also included the caveat that if we went up the first pitch, we’d have to go down if the second pitch was wet, even if we were having fun. The reason is that the second pitch has a section of unprotectable climbing. I was willing to take on wet climbing, but I wasn’t willing to take on wet and unprotected climbing.

Our plan took into consideration that if we successfully passed the second and third pitches, we could rappel from there without having to climb the fourth pitch and top out. This was reassuring in case the fourth pitch looked too wet to climb or if we were fed up and just wanted to go down.

Lastly, the whole plan was formulated on the fact that 5.7 climbing is well within my leading and Whitney’s following abilities, even when wet. And that if there was a sequence of moves that were too wet to free climb safely, I possessed the skills to aid the climb to continue progressing upward. And if the climbing was too wet for Whitney to follow, I possessed the skills to safely assist her upward.

The Climb

Climbing Quadrophenia pretty much panned out according to plan. The protection was ample, and the climbing wasn’t particularly hard. However, I did take a decent amount of time to figure out the crux on the wet first pitch.

I tried a couple of different body positions before committing to the sequence. Everything pivoted off an insecure and wet toe jam I placed in the crack below me. While the handholds were above average, if any one limb slipped, I would have fallen because of how slippery the rock was. The fall would have been okay since I had gear around my belly button. And fortunately, I stayed on.

To our delight, the second pitch was mostly dry. But before castin off, I wanted to be as sure as possible. From our vantage, I could see that the unprotected section was dry. I could also clearly see a crack feature where I would have the opportunity to place protection.

I climbed delicately and smoothly. The rock offered a variety of grip types and elicited engaging climbing movement. Soon, I had ample protection placed in the wall. Towards the top of the second pitch, I was back to climbing on wet holds, but they were so big, and climbing was so intuitive it didn’t matter. Whitney followed in good style.

The third pitch is where things got interesting again. From below, I could see that the climbing was mostly dry except for a wet streak running below the hardest part. The wall was soaked right where I would be placing my feet. But because I was well protected, I tried the sequence.

The handholds were good but directional. I couldn’t just pull down on them. The grips needed to be loaded in specific directions, and proper foot placement was required to create the body shape I needed to stay on. All four limbs needed to function in unison.

Unfortunately, the feet were small and insecure edges. It didn’t take long for my right foot to pop. Losing the intricate body tension I created, I was off in a millisecond. The gear I placed held in the rock, and Whitney arrested my fall without issue.

Instead of trying to free climb the sequence again, I opted to quickly aid through the wet section. Instead of gripping the rock with my fingertips, I placed gear in the wall and pulled on that, like installing temporary monkey bars. After a couple of aid moves, I was back to impeccable climbing on dry stone.

From the top of the third pitch, we reconsulted our plan. Above us, we could see dry rock and what looked to be fun climbing. Plus, despite the wet rock below, the climbing was quite nice. The weather was also on our side, and we weren’t worried about afternoon storms. All in all, we were enjoying ourselves, so instead of going down, we opted to top out.

The climbing that ensued was well worth it. While some of the rock was weak and friable, other climbing holds were awesome hunks of quartz-looking rock. I felt like I was flowing up a steep crystal jungle gym. On the summit, we enjoyed views of Lake Champlain and Giant Mountain.

The Debrief

Climbing Quadrohenia with Whitney did not pan out perfectly, especially considering the route’s condition. I also would have preferred not to have fallen. Not because it was wildly unsafe, per say, but mostly because it would have been better style not to have fallen.

However, any day of climbing is better than no day of climbing.

Most importantly, I was proud of how we worked as a team to assess the climbing objective's plausibility before leaving the ground. It would have been a bummer to turn around and not climb, but I would have done it if the climbing was supposed to be harder. Or if the route was more committing and did not offer opportunities to rappel down.

Throughout the climb, we reassessed multiple times and adequately managed the riskiness of the climb. We never felt like we were especially pushing the envelope way beyond our comfort.

I enjoyed the climbing, and beyond that, I thoroughly enjoyed the challenges that came with navigating the wet terrain. I was focused, solving problems and deploying my advanced set of skills.

In other words, I was doing cool shit, and it felt rad. (It probably looked more rad, but you’ll have to ask Whitney).

All jokes aside, I don’t think I would have been able to dissect a rock climb like we did without the training I’ve had from the AMGA. And I don’t just mean being strong enough to do it.

Deciphering the route beta;

bringing proper equipment;

considering the terrain conditions;

monitoring the forecast;

conceptualizing the various descent options (before leaving the ground);

deploying free and aid climbing techniques efficiently;

and communicating in partnership are examples of the subtle nuances that Whitney and I navigated to be safe and successful.

All without a single argument!

This newsletter is entirely reader-supported. If you enjoy my writing, you can make a one-time donation at Buy Me a Coffee. Your support means a lot. Thank you!