Honeymoon Rock Climbing in Cojitambo

Almost bailing off one of Ecuador's best multi-pitch rock routes

Whenever Whitney and I travel, we tend to gravitate towards oceans or rocks. So, when it came time to plan our winter honeymoon, we naturally sought out a destination that would offer both. We thought maybe South Africa or the Mediterranean coast of Spain. But then my travel instincts for South America began tingling.

After a month or two of research, we decided the best option was Ecuador. Traveling during December in Ecuador's eternal and equatorial springtime would offer cooler temperatures at elevation in the Andes (or so we thought), perfect for rock climbing, and ocean swells on the Pacific coast, perfect for surfing.

So after flying into the country’s capital city of Quito and enjoying urban attractions like Quito’s Botanical Garden and one of the finest eight-course meals we have ever experienced at a restaurant called Somos, we flew south towards Cuenca in search of stone.

Cuenca’s Rock Climbing Epicenter: Cojitambo

In the southern part of Ecuador, outside the region’s capital city of Cuenca, is a small town called Cojitambo.

When I began researching about Cojitambo (or Coji as the locals call it) months ago, I remember being impressed by the sheer size of the formation. However, I also remember feeling a bit in the dark about the climbing– there just wasn’t a ton of information online.

Undeterred, Whitney and I went to Coji on the premise that a piece of rock that big would have to have enough decent rock climbing to keep us busy for four days.

We were wrong about the quality and quantity of climbing Coji provided in the best way possible.

A Sacred Mountain

Coji is one of four mountains in the area– representing the Western cardinal direction. The other three are Abuga, to the north, Fasayñan to the east, and Guaguashami in the South. In pre-Incan and Incan times, Cojitambo was heralded as a sacred space. It’s said that the mountain and surrounding areas represent the three worlds of the Andean worldview– Hanan Pacha (heaven), Kay Pacha (Earth), and Uku Pacha (the underworld).

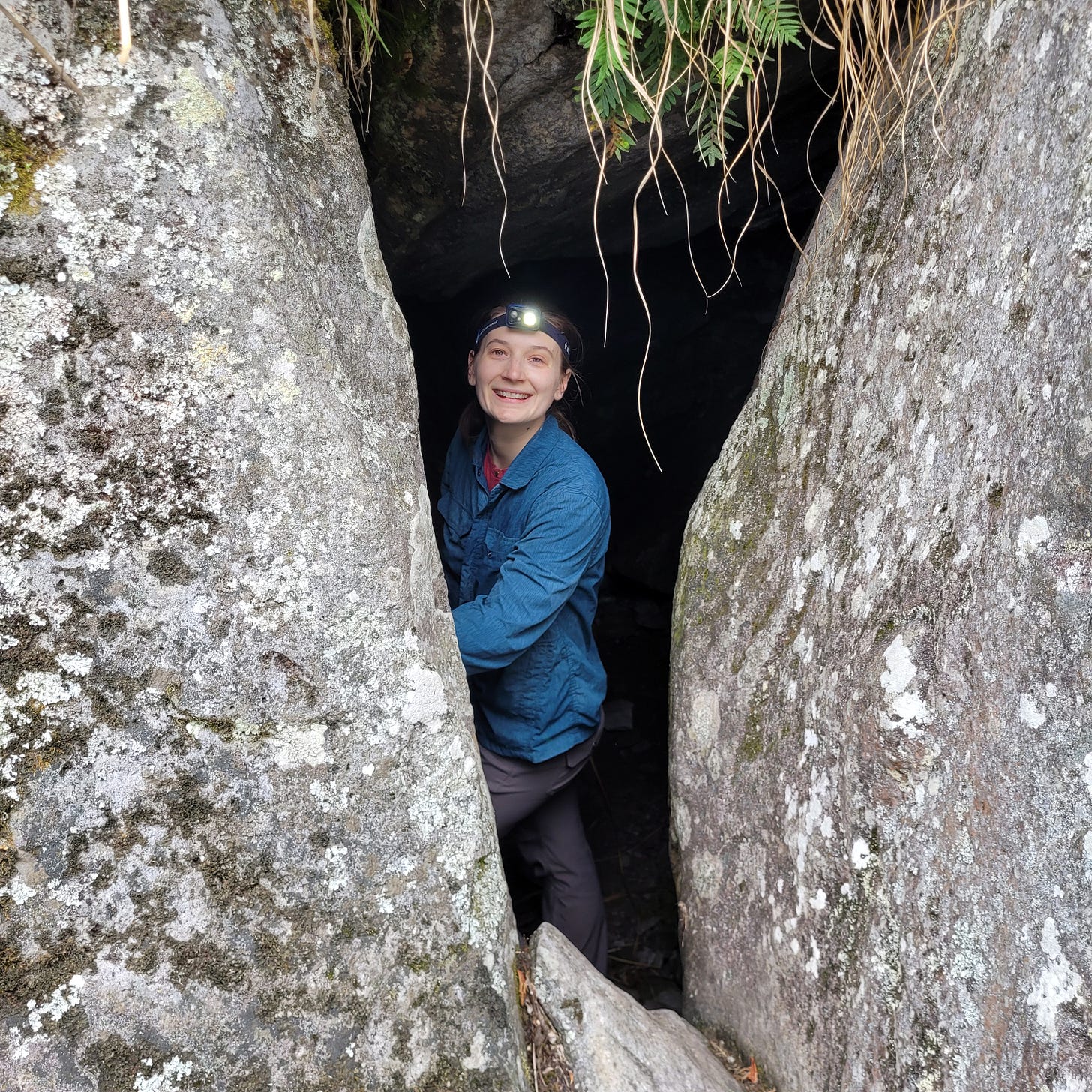

During our stay, we dabbled in all three worlds. We summited into the heavens via long multi-pitch routes, explored the earthly base of the mountain while single-pitching, and even entered the underworld via the Mashu Juktu cave.

Legend has it that the Mama Waka attracts young men to the cave with her golden treasures only to absorb their youthly life force so that she may live longer.

Fortunately for us, we did not cross paths with Mama Waka during our spelunking.

Modern Day Cojitambo

Cojitambo is still a significant place but in a different kind of way.

The craggy bottoms of the cliff are an indispensable resource for mining. On most days, miners can be seen and heard making cobblestones by hand. The stones are transported to Cuenca to be used for making streets. Meanwhile, local farmers use the fertile countryside to plant their crops and raise animals.

And, of course, climbers enjoy Coji for its incredible rock climbing.

The Climbing in Coji

The mountain of Cojitambo is an old volcanic plug or neck. That essentially means that Coji is the solidified remains of an old volcano that has all but been eroded away. What’s left is the hardened magma from the interior of the extinct volcano that we climb on.

The rock, or hardend magma, is andesite. The andesite rock made for some really exceptional climbing. Most of the climbing we did in Coji was low-angle and slabby. Although, there are some really steep overhanging walls with many hard climbs and open projects.

The majority of climbing is bolted sport climbing, including the multi-pitches. However, there were plenty of traditional lines to climb. But I must admit, I did not deploy my trad rack– clipping the bolts was just too much fun.

The movement the rock created was like a delicate dance with improbable steps. Each time I would eye up a sequence of moves based on the rock features I had before me, I would doubt that it would work.

But as I pasted my feet onto tiny foot chips and crisp edges, pulled on small finger pockets, and linked together large huecos and flake features, I would find myself utterly entertained by the puzzle that I was solving with my four limbs.

Locals Love Coji

The development of rock climbing in Cojitambo has been a labor of love since the 1980s and 90s. Legendary local climbers like Daniel Carrion and Juan Gabriel Carrasco poured endless labor hours and bolts into the cliff for the benefit of other climbers, all for free, except in 2013.

In 2013, in an effort to catalyze rock climbing-related tourism, the government of Ecuador gifted a grant to route developers like Juan and Daniel. With the grant, developers established 200+ new routes all over Ecuador. And they were finally reciprocated for their labor of love. In Cojitambo, 50+ new routes were bolted, one of which was La Langarota.

Juan Gabriel was also our welcoming host. During our time in Coji we stayed in Juan Gabriel’s home and had the privilege of relying on him for fantastic conversations about indispensable climbing beta and local cultural knowledge. With the help of Juan Gabriel’s knowledge, our time in Coji was infinitely more authentic and memorable.

La Langarota–Coji’s Crown Jewel

You cannot look at Cojitambo without seeing La Langarota. It’s an obvious line that links the bottom of the cliff with the highest point on the mountain. Its name, which is slang for a long or tall and skinny person (langarote/a), comes from the obvious fact that it is one of Coji’s longest rock climbs.

In fact, it’s Ecudaor’s second longest rock route. The other is a new line that climbs Coji’s southern ridgeline to the summit in 12 pitches.

La Langarota is an 8-pitch, 220-meter climb (~720 feet) that traverses diagonally from left to right and then straight up to the summit. The bottom half of the climb follows a never-ending slabby ramp. The ramp is mega-exposed and requires confidence in tiny pockets and small edges. When the features run out, you must be able to smear in dishes and balance your way upward without much for handholds.

The second half of the climb transforms into steep corner climbing and overhanging jug hauling. Stemming through the bottomless corner on edges and smearing is required. Through this section, technique is everything.

Above the corner, the rock gets steeper and overhanging. You have to navigate multiple blocky bulges and overhangs and manage the exposure from being over 500 feet off the deck.

To exit, you transition from rock to dirt and trample your way to the top, hoping that the root systems of the small plants you are yanking on stay connected to the crusty soil.

Our Climb Up La Langarota

We decided to climb La Langorta on our second day in Coji. We woke up to perfectly sunny skies over Coji, although we knew a rainstorm would arrive in the afternoon. So we quickly set off into the sol de aguas after breakfast.

I carried a climbing pack with gear, water, sandwiches, and obligatory rain jackets. Whitney hauled the rope.

From where we were staying, the base of the climb was only about one mile away. But it was purely uphill, and the altitude (over 9,000 feet above sea level) was striking. Various old mining access trails mixed in with climber’s trails made the navigation tricky.

Fortunately, our surroundings were stunning– we hiked through overgrown trails decorated with pink orchids and purple flowers, listened to songbirds, and watched peregrine falcons fly over our heads.

Soon, we found a clearing at the base of the cliff with a line of bolts leading us upwards. We flaked the rope, strapped on our shoes, and left the ground.

La Langarota faces east, so by the time we were three pitches off the ground, the morning sun had begun to take its toll. Our feet wrapped in leather and climbing rubber were steaming. Whitney, after arriving at the anchor system, began to feel lightheaded.

Hanging in our harnesses at the belay, wary of heat exhaustion and being teased by the shade beckoning us to the ground, we contemplated going down.

We knew bailing down was an option– the bolted rappel anchors could facilitate an easy evacuation. But the stressors of “wasting” a precious day of climbing during our limited time on our trip seemed like a severe punch in the cajones (pardon my Spanish).

Plus, bailing up would be more fun. So, after some contemplation, we finished off our electrolyte-dosed water, ate a bar, and poured more water into our helmets and onto our necks to cool off. Soon, we began to equilibrate, and up we went.

Pitch after pitch, the prospect of the summit being closer motivated us, and the pressure from bailing off our objective diminished. And despite the heat, the delicate and thought-provoking climbing kept us thoroughly entertained.

Eventually, we were at the summit of Cojitambo.

With all 700 feet of climbing behind us, we could relax a bit, enjoy the view, and bask in the feeling of having achieved our goal despite having doubted the objective.

Down below us, the quaint town of Cojitambo radiated in the Andean heat. On Coji’s second summit, a pair of climbers were sitting, sharing our view. And far off to the east, in the direction of the Amazon basin, dense and opaque storm clouds were forming, reminding us to enjoy the top but enjoy it briefly.

So we drank more water and enjoyed the sandwiches we transported to the top, reminiscing about our favorite pitches and reflecting on the discomfort we experienced.

Eventually, we changed our shoes, readied the rope, and began our hike to the rappel station located in the col between Coji’s two summits. Two rappels would get us down to the ground, back amongst the cool shade of the cliff and the capulin trees, and only half a mile away from cold beer back in the plaza.

Epic climb and even more epic people. Glad you enjoyed the honeymoon!!! <3